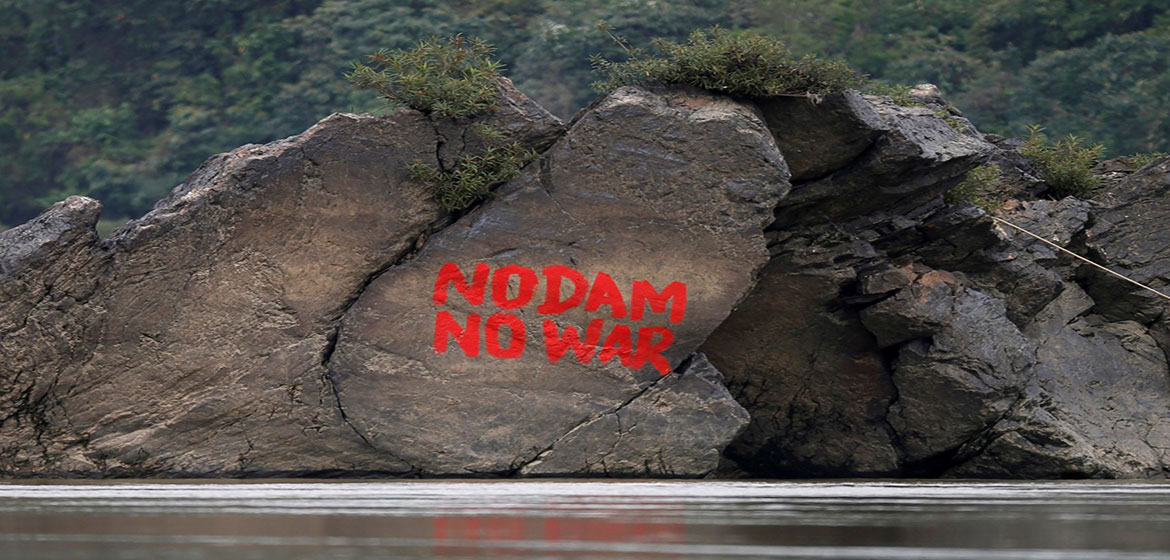

- If Myanmar’s leader goes ahead with the long-stalled, multibillion-dollar dam she will face the wrath of displaced communities at the ballot box

- Back out, and she risks driving away the Chinese investment on which her country has become increasingly reliant

By Oliver Slow

For Lu Ra, 55, growing up in Tanghre village, on the eastern banks of the Irrawaddy River in Kachin State, meant a life relying on Myanmar’s biggest waterway for most of her daily activities.

“I had lived my whole life there, and that village was very special to us,” she said. “My father made his living from fishing at the river, and we grew many crops and sold them in the local market.”

But in 2011, Lu Ra was told she would need to leave her village and move 8km south to Aung Myithar, to make way for the Myitsone Dam, a multibillion-dollar China-backed project that was being planned on the river. “Nobody here wants that dam,” said Lu Ra, speaking at her neighbour’s home in Aung Myithar. “Where it is located is a very special place for our people, at the joining of two rivers to form the Irrawaddy. That river is the bloodline of our country, and will be ruined if this project goes ahead.”

Lu Ra, who was displaced from her home in Tanghre to make way for the Myitsone project, speaks at her neighbour's home in Aung Myithar village. Photo: Oliver Slow

The Myitsone Dam, the largest of seven hydropower projects planned on the Upper Irrawaddy, has been shrouded in controversy since it was first mooted in 2009 when Myanmar was under military junta rule.

Estimated at an initial cost of US$3.6 billion, the project was announced as a joint venture between the China Power Investment Corporation (CPIC; now State Power Investment Corporation) and Myanmar conglomerate Asia World Company.

Kachin people protest against the Myitsone Dam project. Photo: EPA

However, in a move that surprised observers, shortly after coming to power in 2011 then President U Thein Sein announced the project would be suspended for the remainder of his term. At the time Lu Qizhou, president of CPIC, told Chinese media that he was “totally astonished” by the decision.

The issue has now been pushed onto the agenda of National League for Democracy (NLD), which took power in 2016, but a decision has still not been made about the future of Myitsone.

When Suu Kyi visited Kachin State on the campaign trail ahead of the 2015 election that brought her party to power, she stopped short of promising to put an end to the dam, but said she would make the details of the deal public. “I don’t want to make any promises now because we still don’t have any idea about it either,” she said. “We all have to find an answer for it when we reveal it.”

However, as her party’s first term nears its end and a crucial election looms next year, people in Kachin State have accused Suu Kyi of not listening to their voices, and say they will instead speak at the ballot box.

“Aung San Suu Kyi used to stand for the people before she came to power, but now she doesn’t,” said Ja Hkawn, who was also displaced from Tanghre because of Myitsone. “If the situation stays as it is, no one here will vote for the NLD.”

A group of women displaced by the Myitsone project gather at the home of Ja Hkawn in Aung Myithar village. Photo: Oliver Slow

However, the government must balance the general population’s animosity towards Myitsone – something that is not limited to Kachin State, but nationwide – with the wishes of China, which continues to lobby for the project to be given the go-ahead.

In January, the Chinese Embassy in Myanmar issued a statement saying that if the Myitsone issue failed to be resolved it would “seriously hurt the confidence” of Chinese investors in Myanmar.

Associate Professor Zhu Xianghui of Yunnan University wrote in a paper recently published by Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute that the suspension of the Myitsone project had made China rethink its approach in Myanmar, recognising that its neighbour was “not a powerless state”.

After the suspension, Chinese direct investment in Myanmar tumbled from US$8.56 billion in 2011 to below US$2 billion last year, he said, as Beijing took a more “conservative and low-profile approach” to economic engagement.

Still, China sees Myanmar as a crucial component of its ambitious to boost global connectivity.

In September last year, both sides signed an agreement for the China Myanmar Economic Corridor, connecting Yunnan Province with Mandalay, the biggest city in Upper Myanmar, then onwards to Yangon and Kyaukphyu, in Rakhine State, where a China-backed deep seaport is under construction.

Children gather at the confluence of the Mali and N’Mai rivers, which forms the Irrawaddy River, Myanmar’s largest waterway. Photo: Oliver Slow

Myanmar is also heavily reliant on China. Although the reforms that began in 2011 were regarded as a move by the Myanmar government away from its reliance on China and closer to Western countries such as the , in recent years Naypyidaw has drifted closer to Beijing, as a result of widespread international criticism of its treatment of the minority in Rakhine State. China has consistently offered Myanmar “strong support” on this issue.

Yun Sun, co-director of the East Asia programme and director of the China programme at the Stimson Centre, believes that a cancellation of the project along certain terms could be beneficial for both governments.

People from Kachin State protest against the Myitsone dam project. Photo: AFP

“The cancellation itself does not necessarily mean enduring and critical damage to bilateral relations,” she said.

“The key lies in what happens to the disbursed investment and interests it has accumulated. If Myanmar just cancels it without any compensation, that will not be good for bilateral relations. I have always called for its cancellation on mutually acceptable terms and for the two countries to move on,” she said.

As the election nears, there is still no indication as to whether the project will be allowed to go ahead, although in a speech in March Suu Kyi hinted it could by urging people to take “a wider perspective” on the issue.

Monywa Aung Shin, a member of the NLD, said he did not know what the government’s decision was, and that Suu Kyi, as well as members of the party’s Central Executive Committee, would decide.

“The Myitsone Dam project is important for [the Belt and Road Initiative] and the China Myanmar Economic Corridor. If we implement the [economic corridor], we need foreign investment. We can’t implement economic zones without electric power,” he said, adding that those were his personal views and not those of the party.

Zhu, from Yunnan University’s Institute of Myanmar Studies and the School of International Relations, said Chinese state-owned firms were under pressure to adapt to the “new political climate” in Myanmar and had begun to change their behaviour, for example by conducting public relations activities and taking some measures to address the environmental and social impact of projects.

Zhu argued that Chinese firms had diversified the industries they were investing in, including in manufacturing, infrastructure, connectivity and energy projects such as wind and solar.

He said the result of next year’s election would affect China’s approach in Myanmar, arguing that Beijing would “pay close attention to the outcome for signs of how it should proceed with future investment projects”.

However, back at Aung Myithar, the women displaced by the project are yet to be convinced by this change in approach and have said they will continue to campaign for it to be cancelled, and hope one day to be able to return home.

“This project should not happen, it is impossible,” said Ja Aung, 36. “There is no reason for us to accept this project, nobody wants it.”

This Week in Asia has reached out to both the State Power Investment Corporation and Asia World Company for comment.

Source:

Related to SDG 10: Reduced inequalities and SDG 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions