By Gladson Dungdung

On 13 February 2019, the Supreme Court of India while hearing on the Writ Petitions (c) No. 109/2008 Wildlife First & Ors Versus Ministry of Forest and Environment & Ors, passed an order for eviction of the Adivasis and other traditional forest dwellers, whose claims have been rejected under the Forest Rights Act 2006. The Court directed that where the verification/ reverification/review process is pending, the concerned state shall do the needful within four months from today and report be submitted to this Court. Let Forest Survey of India (FSI) make a satellite survey and place on record the encroachment positions and state the positions after the eviction as far as possible[1]. However, on 28 March 2019, the Court stayed its controversial order after the intervention petition was filed by the Central government for modification of the order apprehending its consequences on the general election. The government in its plea said that the forest dwelling scheduled tribes and other traditional forest dwellers are extremely poor and illiterate people and not well informed of their rights and procedure under the Act. They live in remote and inaccessible areas of the forest. It is difficult for them to substantiated their claimed before the competent authorities[2] therefore their claims were rejected.

The Court ordered the Chief Secretaries of the state governments to file detailed affidavits covering all the aforesaid aspects and place on record the rejection orders and the details of the procedure followed for settlement of claims and what are the main ground on which the claims have been rejected[3]. The court said that it may also be stated that whether the tribals were given opportunity to adduce evidence and, if yes, to what extent and whether reasoned orders have been passed regarding rejection of the claims[4]. The Court also ordered the Forest Survey of India to make a satellite survey and place on record the encroachment positions as far as possible before the next hearing[5]. In this circumstance, there is an apprehension of eviction of Adivasis and other traditional forest dwellers from the forests if the Supreme Court orders to execute its earlier order in forthcoming hearings. There would be eviction of more than 2 million Adivasis and other traditional forest dwellers from the forest land and forests. Therefore, we should analysis some cases to understand the impact of eviction. Kudagada is one such examples.

Kudagada is a revenue village comprised of 8 hamlets (Kudagara, Bardanda, Garurpiri, Heso, Fatehpur, Nimdih, Modotoli and Jogitoli) located in the Heso forest, falls under Namkum development block in Ranchi district of Jharkhand. There are 347 households with the population of approximately 1500[6]. The village is dominated by the Munda Adivasis, whose livelihood is based on agriculture and forest produce[7]. The most of the Adivasis own some patches of revenue land and some of them also cultivate on the forest land, which they have prepared for cultivation but don’t have entitlement papers.

When the villagers came to know about the Forest Rights Act 2006, which was enforced to recognize their rights on forest land and forest, they formed a ‘Forest Rights Committee (FRC)’ under the Kudagara Gram Sabha (village council). 36 villagers filed claim forms and submitted to the FRC[8]. The Kudagara Gram Sabha verified the claims and sent those with recommendations to Dr. Sweta, the Circle Officer of Namkum, where most of the claims were rejected and only 6 claims were converted into entitlements with small patches of land.

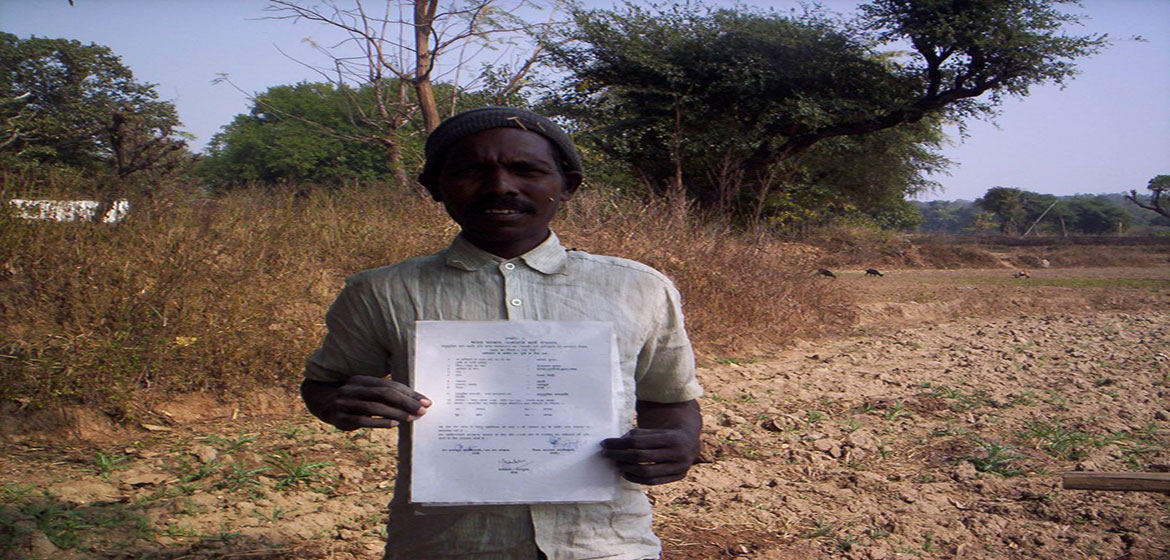

Interestingly, the claim of the chairperson of the FRC, Purandra Munda was rejected along with 29 others. Munda had filed claim of 1.5 acres of land. The 6 villagers, whose individual rights were recognized and given pattas (entitlement papers) are also upset because the area of land were decreased in the pattas though they have been cultivating and possessing the land for generations. For instance, Bando Munda, who had filed claim on 8 acres of land but given patta of merely 7 decimals of land[9]. Similarly, Somra Munda was given patta of 2 decimals for the claim of 2 acres and Budhram Munda also given patta of merely 2 decimals of land for 2 acres. Bando Munda is upset and angry for denying his rights. He says, “We have been cultivating on eight acres of forest land for three generations but I was given entitlement of merely seven decimals of land. How can my family survive with such small patch of land? This is injustice to me. I’m not going to leave my land.”

The villagers had also filed claim of 700 acres of forest under the community rights but their rights are not yet recognized. The circle officer had asked them to decrease the area of forest in the claim form from 700 acres to 100 acres but they refused to do so therefore, the claim file was deliberately misplaced in the office of CO and they had to file it again. Chairperson of the FRC, Purandra Munda says, “We depend on forest for our survival, therefore, we cannot even imagine our life without forest. We should be given the entitlement of 700 acres of forest, which we have been utilizing and protecting for generations.” In this case, if the SC’s eviction order is enforced, the genuine claimants of the forest rights will not only lose their cultivated land but they will also lose the community forest, which plays a vital role in their economy and entire life cycle. This is the biggest threat to their existence.

The eviction order of the Supreme Court will have adverse effect in the life of more than 2 million forest dwellers mostly the Adivasis of the country. According to the FRA status report as per 30th November 2018, 4,224,951 including 4,076,606 individuals and 148,345 community claims were filed. Out of these claims, 1,894,225 including 1,822,262 individuals and 72,064 community pattas were issued whereas 1,939,231 claims were rejected and 391,495 claims are in pending[10]. Therefore, if the SC’s order is enforced, 1,939,231 families will be chased out of the forests. A billion-dollar question is where will they go? Who will protect their fundamental right to life? The Indian constitution guarantees the right to life to everyone under the Article 21 and the State is duty bound to protect it. Unfortunately, the State has failed to protect the rights of the Adivasis and other traditional forest dwellers primarily because it intends to grab the remaining natural resources (land, forest and minerals) from them and hand it over to the Corporate Sharks.

Source:

Related to SDG 10: Reduced inequalities and SDG 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions