By Mary Halton

Indigenous peoples around the world have understood the stars, tides and local ecosystems for hundreds of years but experts say their . Now some female scientists are striving to highlight their achievements and collect the scientific heritage of their communities before it disappears.

From Australia to Canada, detailed scientific knowledge of the natural world has been handed down through generations via stories and oral tradition.

But this information is rarely formalised or even distributed beyond small communities.

And its significance within the wider culture of science goes largely unacknowledged, argues Australian astronomer Karlie Noon

Many textbooks will attribute discoveries to specific Western scientists, "and yet we have physical evidence that contrasts that".

Ms Noon graduated from the University of Newcastle in New South Wales, Australia with a joint degree in maths and physics, and has since set about documenting the scientific knowledge of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The Yolngu people, she notes, knew that the tides varied depending on the phases of the moon. Her own people, the Kamilaroi, have a rich astronomical heritage, which Karlie did not encounter until her early 20s.

The knowledge she has now collected shows a keen understanding of meteorology. A moon halo - a bright ring visible around the moon when there are ice crystals in the air - was used by indigenous peoples all over Australia as a weather predictor.

NASA, ESA AND AURA/CALTECH

Oral tradition tells of counting the number of stars between the moon and the halo, to indicate how much rain there would be. Fewer visible stars meant greater precipitation, which, Karlie agrees, would tally with the presence of more water vapour in the air.

Variable stars, whose brightness fluctuates over periods that can range from 100 - 200 years, are also described in stories.

What is 100 Women?

names 100 influential and inspirational women around the world every year. This week marks 150 years since the birth of Marie Curie and we are celebrating women in science all week. Join us on , and , and let us know about your favourite scientists on #100Women

Karlie notes that being able to pick up these changes through generations, and without the aid of visual magnification, means that these peoples were "amazing observers and astronomers".

The Maori peoples of Aotearoa [New Zealand] also had a detailed knowledge of astronomy, says Ocean Mercier, a senior lecturer at Victoria University in Wellington.

Their knowledge was quite localised, to the extent that names for the stars could differ even between iwi, or tribes.

Descended from the Polynesian voyagers who travelled to the islands of Aotearoa, Maori scientific knowledge also has a rich tradition in wayfinding, or navigating by sea.

"The Earth itself was the compass," Dr Mercier notes. "The ocean gave the signs for wayfinding."

Stories tell of wayfinders travelling as far south as Antarctica, encountering "white rocks coming out of the sea".

Unlike the history of Western science, the role of women as knowledge keepers has always been highly valued in Maori society, says Dr Mercier.

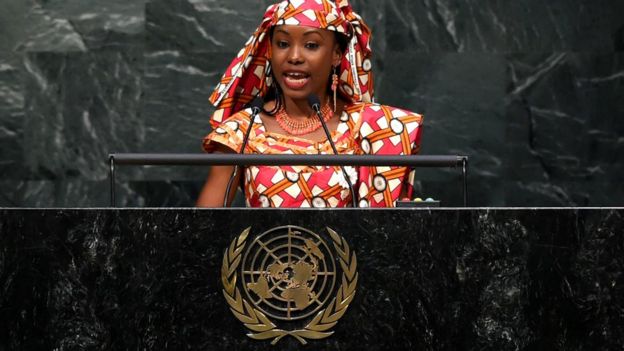

Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim addressing the UN Opening Ceremony of the High-Level Event for the Signature of the Paris Agreement last year. GETTY IMAGES

Though there were and still are gendered roles when it comes to particular branches of knowledge, this has the flexibility to vary between iwi, and women play a vital part in the oral tradition, she says.

In Chad's nomadic Mbororo community, women have not traditionally held positions of power or influence. However Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim has been in the habit of defying convention since she was a child.

Her mother faced a fierce backlash for educating her children, sending "even the girl" to school.

Now just , the country's largest body of water, Lake Chad, is a vital resource for people from Chad, Cameroon, Niger and Nigeria. It has diminished vastly in Ms Ibrahim's lifetime and the seasons on which her people depend to care for their cattle are changing rapidly.

"We used to have three seasons - the rainy season, the cold season and then the dry season. Now we do not have a cold season. The rainy season has become very short," she explains.

Seeing the impact of climate change, which disproportionately affects women and children, who must walk farther and farther to fetch water, Hindou took matters into her own hands.

Hindou Oumarou Ibrahim is documenting the changes in Lake Chad. AFP/GETTY IMAGES

She initiated a 3D mapping project, combining modern technology and the traditional scientific knowledge of her people. Using indigenous understanding of the local landscape, water resources and plant life, a physical model of Baibokoum, a region in the south of Chad, has been created.

This demonstrates to local authorities how well the Mbororo understand their environment, and involves them in planning for its future.

Ms Ibrahim also campaigns internationally on behalf of her people, highlighting the risk of conflict that climate change is creating in nomadic societies because they are being forced to move into new areas in search of pasture.

She has become a leader in her own community, and hopes to inspire more women to do so.

"When they hear... what a little indigenous girl coming from the communities has done… maybe it can give them more courage to fight for women's rights."

Ms Noon and Dr Mercier are both passionate about encouraging indigenous people, and specifically women, to participate in the world of mainstream science.

Though indigenous interest in science subjects is high in Australia, and much is being done to improve access, Ms Noon observes that this has not yet translated to a representative enrolment rate at university.

Dr Mercier is hopeful that Western science and traditional knowledge will find a balance.

"Every culture has a science. So it's really important for the indigenous voice to be there."

Source:

Related to SDG 5: Gender equality