By: Laura Notess & Peter G. Veit

Land conflicts can be fatal for burgeoning agribusiness or other enterprises located in rural regions, but many companies have limited knowledge of how to anticipate and evaluate land-related risk. This is particularly true for land held under collective arrangements by Indigenous peoples or other communities, which is seldom formally documented.

Vacant Land, or Invisible Risk?

Governments eager to attract new investments may advertise large swaths of ostensibly vacant land. Companies should be wary of this promise: Rural communities often have customary rights to land that, at a casual glance, looks like empty wilderness. Forests, pastures, wetlands, and other common areas serve purposes that are not always readily apparent, such as providing a source of food, water, fuel, and medicinal plants; supporting hunting, fishing, or small livestock grazing; or serving as sacred or burial grounds. Over decades or even centuries, communities have developed management practices to ensure these common resources can sustain community life.

Most community land is not formally recorded in government registries or acknowledged via formal legal documents. Although communities hold as much as 50 percent of the world’s land under customary or community-based arrangements, national laws only recognize their claims to , and even less is formally registered and documented.

Accordingly, companies cannot rely on a simple title check to screen for community land rights. But failing to account for these lands can pose serious legal and other risks. Legal risks arise where national laws protect customarily held lands even if they are not formally documented. For example, ancestral lands of Indigenous peoples may be constitutionally protected even if they are not entered into any government property registry.

Other risks are also present, as companies that fail to rigorously screen for land issues may cause to a community, including decreased food security, water stress, and a loss of identity and culture. Serious and sometimes violent conflicts can result: of all disputes between investors and communities in Africa occur when communities are displaced from land. Acquiring disputed land can be expensive, time-consuming, and damaging to a company’s reputation.

The Problem of Identifying Community Lands

The lack of clear documentation of community lands is not just a problem for potential investors: Many communities see formalizing their land rights as they can use to improve their land security. But the process for doing this is often complex and burdensome, as illustrated in a , which compares how communities obtain formal land rights with how companies acquire investment land across 15 countries. It finds that communities can spend decades trying to obtain a title or land certificate. Many others are never able to start the process, lacking financial and technical support or excluded by strict evidentiary criteria.

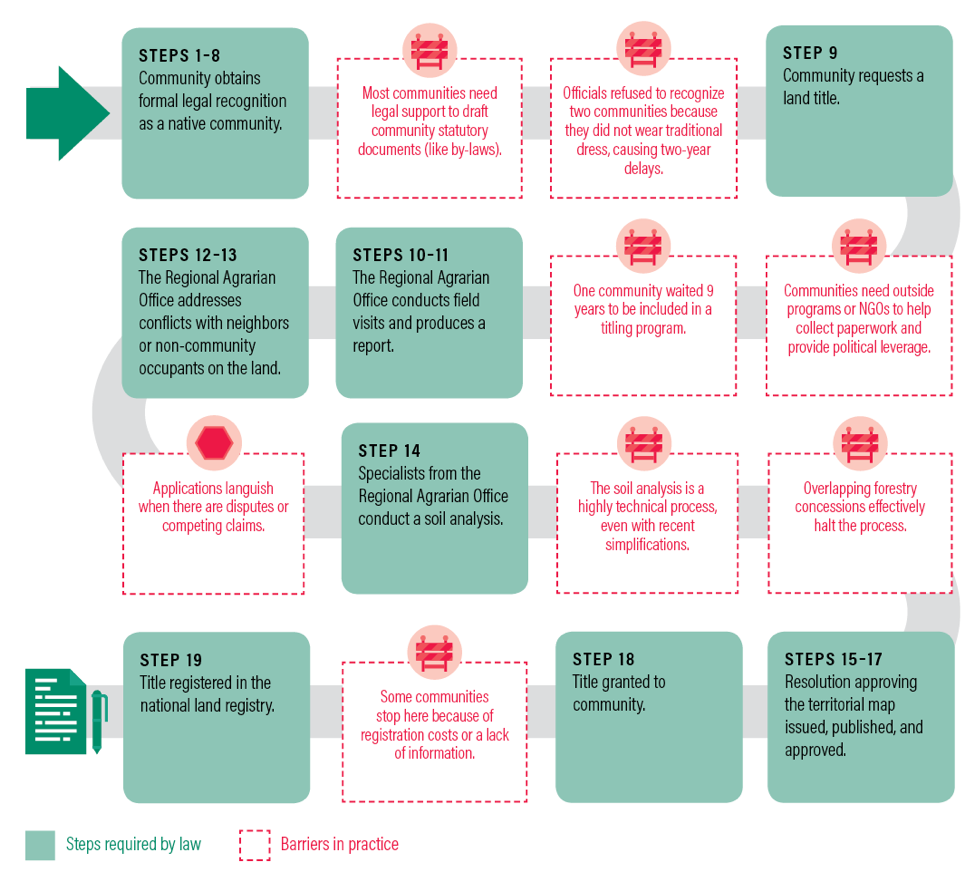

Communities can also face significant administrative barriers: In Indonesia, Indigenous peoples must lobby regional legislatures to be recognized as an indigenous community before even beginning the process of obtaining a land title. In Uganda, communities must incorporate themselves into an association, elect officers, and write a constitution. Communities may not have the expertise or resources to overcome these barriers, as illustrated by this diagram of the legal requirements and barriers in practice, experienced by Peruvian Indigenous communities seeking a community title:

Figure 1: Obtaining a Native Title in Peru: 19 Legally Mandated Steps and Additional Barriers in Practice

Source: CIFOR, modified and simplified by WRI

Even where a community has a land title, companies cannot assume that this accurately captures the entirety of that community’s land. Significant pieces of customary land are regularly excluded from titles granted to communities. In some countries, legal restrictions force communities to fragment their land when they formalize it, excluding certain types of land, such as forested land. Elsewhere, mapping errors result in incorrect borders, or government officials impose arbitrary caps, deeming community lands to be “too large.”

This gap between the formal recognition of community land rights and the reality of customary land use sets the stage for land conflicts between new investment projects established on ostensibly unoccupied land.

Inconsistency in Mitigating Land Risks

Companies are not well-prepared to address land risks related to community land held under informal arrangements. This is partly because the regulatory frameworks that govern land and natural resource concession allocations inadequately address underlying land issues, despite the fact that—as one 10-country study demonstrates—as many as percent of concession territories designated for commercial use already have people living on them.

The WRI report finds that land acquisition procedures for companies can also be complex, but the sources of this complexity are regulations governing environmental or technical permits, not those related to land issues. Across 14 company land-acquisition procedures that the report surveys, all but two have a legal presumption that the land belongs to the government. As a result, less than half of the procedures require any sort of consultation with communities about land issues. Even where consultations are required by law, they are rarely rigorous. This means that there is broad variation in the extent to which investors actually engage with communities about land, such as in Mozambique:

Figure 2: Variations in Company Consultations with Communities in Mozambique

Source: WRI, referencing Di Matteo and Schoneveld 2016; Ghebru et al. 2015; Hanemann 2016

Some companies take in other areas as well. In multiple countries, there are instances of companies beginning commercial operations before they obtain final land rights, or using one legal procedure to access resources governed by a separate, stricter legal regime. In the short term, such companies may have a competitive advantage over those that take the time to engage with community land claims. Such action risks skewing the competitive environment and pushing entire industries to engage in similar behavior. But in the long run, when land disputes inevitably arise, such projects will be unsustainable.

A Way Forward

Companies concerned about mitigating risk and establishing positive relationships with communities should take the time to address land issues up front, even if not required by law. This requires more rigorous engagement than a mere title check. Visiting the investment site, regularly communicating with communities living on and near the land, and obtaining consent from customary owners is key. In addition, companies could work together to press for laws that enable communities to obtain formal recognition of their land rights. Without this, companies will find that the blank spaces on maps hold hidden land-related risks.

Source:

Related to SDG 10: Reduced inequalities and