Global hunger for resources is driving the destruction of indigenous land. On World Indigenous Peoples' Day, campaigners warn that, without action, we risk losing a key part of what makes our planet and humanity diverse.

Deforestation and land grabbing are major challenges confronting many of the 370 million indigenous people worldwide.

They are protectors of 80 percent of the most biodiverse areas on Earth, but activists warn many groups' livelihoods from multinational corporations, conflict, and even nature conservation organizations. The increasing effects of global warming are only making the situation worse. =

Indigenous peoples are immensely diverse — according to the United Nations, they are spread across 90 countries, with 5,000 distinct cultures and 4,000 unique languages.

Despite, or maybe because of this diversity, they share many of the same struggles. Whether they live in Australia, Brazil, or Japan, they have shorter life expectancy and less access to services like healthcare than non-indigenous communities. They make up 5 percent of the world's population, but account for 15 percent of the poorest.

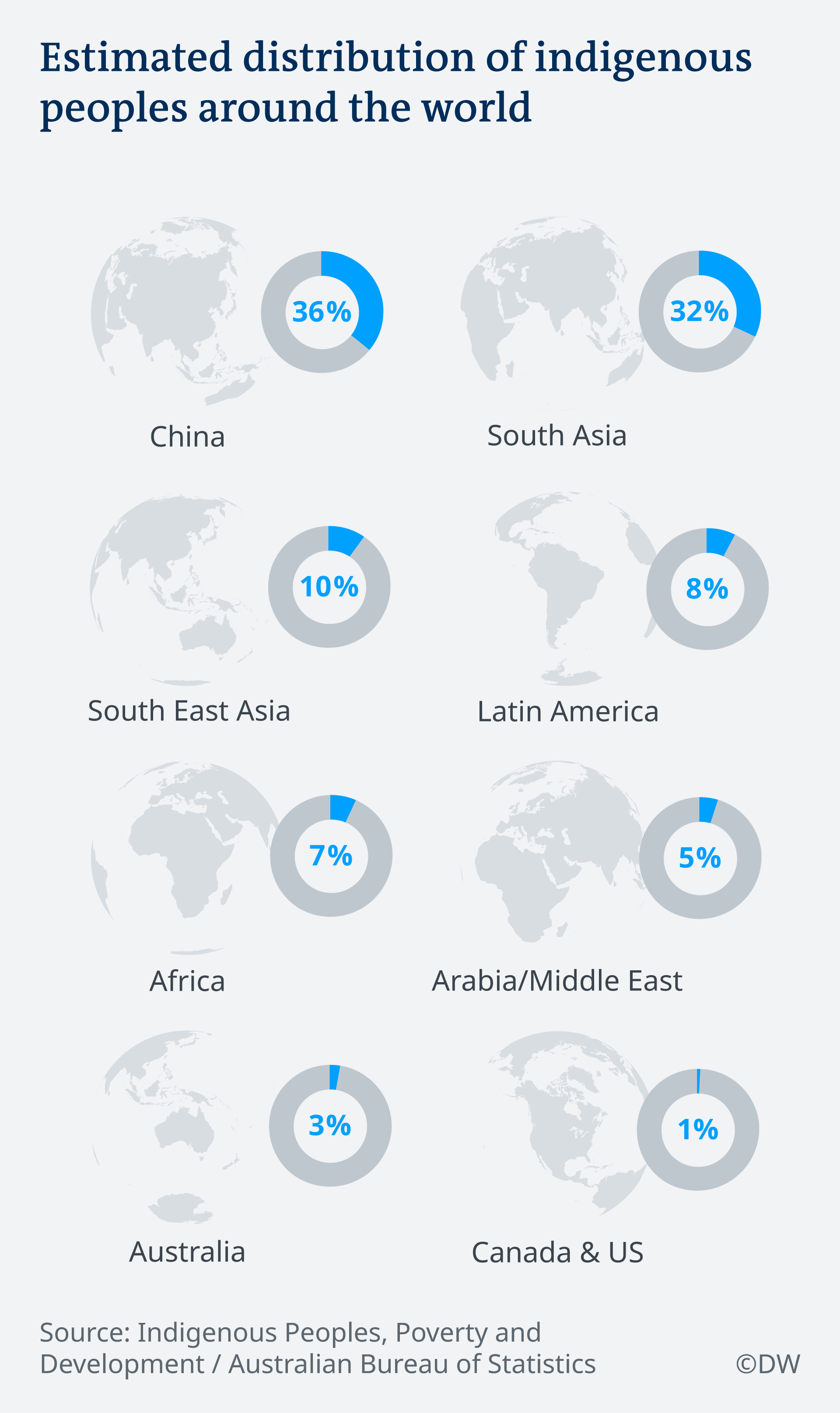

Estimated distribution of indigenous peoples around the world

Loss of lands

Fiona Watson, director of Research and Advocacy at , told DW that one of the biggest challenges many of the different groups face is the loss of their native lands.

"Indigenous and tribal peoples around the world have extremely close relationships to the environment," she said.

"The land is fundamental to their livelihood, their economies, but also they have very deep and profound spiritual relationships to the natural world."

Forced migration

The land grabbing that marked colonial times still happens today, leaving whole groups with nowhere to go, acivists say. Conflict and violence in any form often also encroaches on indigenous land, turning the people into refugees.

Many times, governments play a role by planning new dams or highways through an indigenous area without considering the people living there.

"Indigenous peoples are regarded as 'backwards' or 'primitive' — this is often used by the state, or by multinational corporations, or by whoever…to justify taking over or stealing their land in the name of so-called development," Watson told DW.

Indigenous people protest mining in Latin America

Take, for example, the Guarani people in southern Brazil, who have been forced off their land to make room for cattle ranches and sugarcane for ethanol. They now have one of the highest suicide rates in the world, and "all the biodiversity from their land has disappeared," Watson said.

"Whether the consumer is buying ethanol in the states or in Brazil, many are doing so probably not even knowing that this is at the cost of a whole tribes future."

Paradoxically, Watson says, another significant threat comes from conservation organizations turning land into protected areas without input from the indigenous populations residing there.

"They are creating protected areas in the indigenous territories — their lands that they've lived on for thousands of years — in the name of conservation," she said.

Banned from fishing

There are also clashes over rights in Asia, which is home to 70 percent of the world's indigenous population, according to the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA). The Bajau Laut of Eastern Sabah, Malaysia, are a migratory group that depend heavily on the ocean for their food.

However, their main fishing areas were turned into the Tun Sakaran Marine Park (TSMP) in 2004, and all fishing banned in 2009.

A study conducted in 2017 by the University of Wollongong in Australia found that "[the Bajau peoples'] inability to grow any food on the islands of the park, to which they have no land rights, coupled with the diminution of opportunities to access cash due to restrictions on reef fishing and collecting has decreased their access to essential components of their diet, thus increasing their food insecurity."

Bajau fishermen have been forced to range further from their fishing grounds to find food, or risk being forced to leave the TSMP entirely.

The right to self-determination

The right to make choices for themselves is therefore very important to indigenous peoples, says Watson.

"Basically it goes down to that issue of self-determination — that tribal peoples and indigenous peoples have the right to decide themselves how they wish to live…and this is so often ignored and that’s creating massive problems," she added.

There's no formal definition of "indigenous," even at the international level. Instead, groups are able to decide whether they consider themselves to be indigenous or not.

Naju Dorma, 73, and Lacuo Dorma, 66, from the village of Luoshui, don traditional garb.

The term was cemented in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007, and since then indigenous groups around the world have become more visible. Many international organizations are dedicated to their protection and groups can now raise their voices by going online.

The indigenous Maori in New Zealand are surging in visibility, with sold out Te reo (the Maori language) courses across the country, John McCaffery, a language expert at the University of Auckland, told the Guardian. In Canada, indigenous issues are routinely covered in the media and are part of the national conversation.

These examples show that a functional relationship with indigenous populations around the world is possible. Governments just need to be willing to acknowledge the importance of indigenous communities and negotiate with them on their own terms.

Source:

Related to SDG 10: Reduced inequalities and SDG 15: Life on land